Liberatory Design: an approach to equality

Imagine an urban public school facing persistent challenges of student engagement and educational inequalities. Traditionally, these issues would be addressed with solutions imposed from the outside in, sometimes authoritatively. However, with Liberatory Design, the process changes radically, as it favors initiatives that involve active listening, deep empathy and group-thought solutions. Not in a single, quick step, but in cycles that include adjustments and feedback.

Liberatory Design (LD) is a design approach that seeks to create equitable and inclusive solutions, centered on social justice and the elimination of systemic oppressions, and combines principles of Design Thinking.

The Liberatory Design framework/practice is the result of a collaboration between practitioners exploring the intersection of creativity, design and equity. They are Tania Anaissie (Beytna Design), David Clifford and Susie Wise, from the K12 Lab/ d.School at Stanford University (California) – the K12 Lab serves as a catalyst for creative confidence in K-12 education – and Victor Cary and Tom Malarkey, both from the National Equity Project.

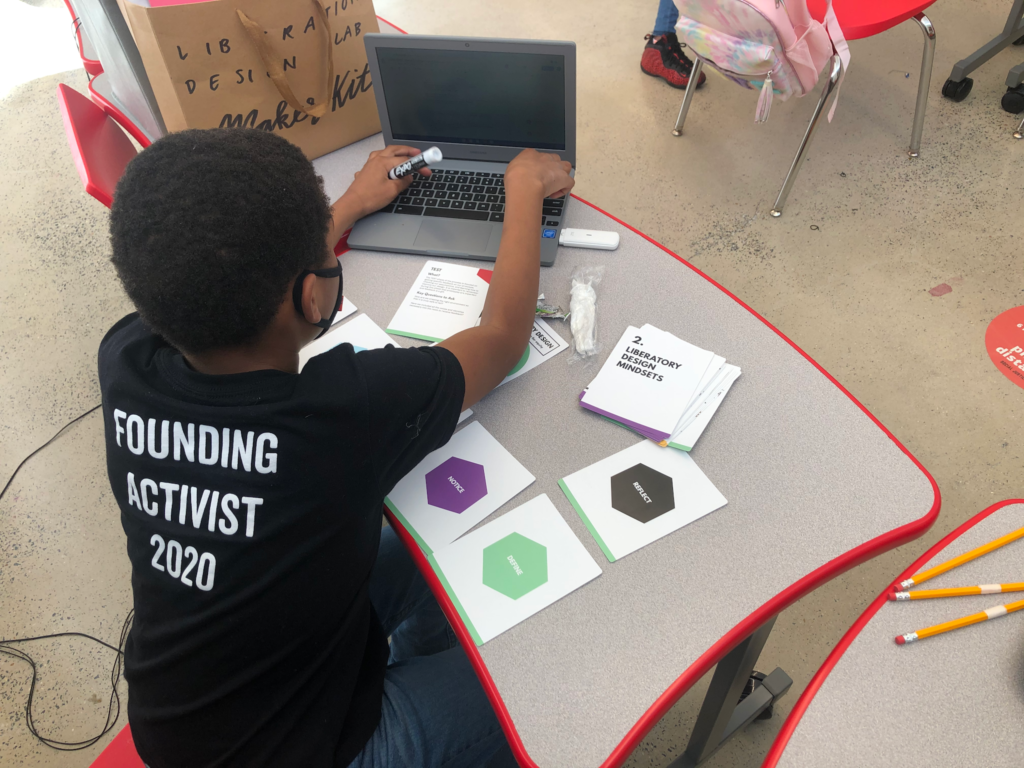

Not surprisingly, Liberatory Design is also available to the Creative Schools community. The material with mindsets and design actions aimed at equity has been translated into Portuguese and can be accessed at this link.

A creative school is also fair, diverse and equitable. Thais Eastwood, a specialist in training and pedagogical innovation at Escolas Criativas, stresses that the approach is very much in line with the dimensions that make up a creative school (you can access the document here) and, as further reference and support material, can help to improve the work underway in the 16 public education networks that are committed to bringing more purpose to education.

“For example, when I design a lesson or a learning experience, is the subject matter relevant? Doesn’t it have, for example, mistaken biases? Am I going to provide a moment of creation or prototyping in this lesson? If so, how can it involve everyone and be an emancipatory experience? Is everyone being listened to? The mindsets of Liberatory Design bring these thinking routines and not prescriptions of how to do things, they bring questions and provocations,” explains Thais.

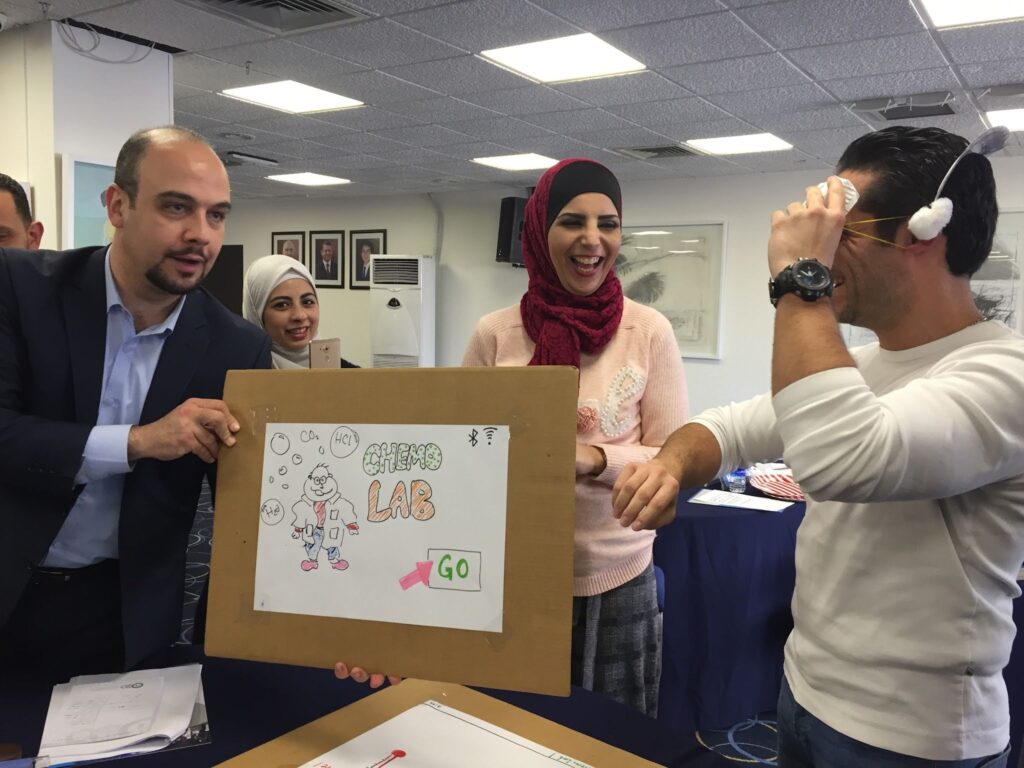

David Clifford, co-creator of Liberatory Design, notes that the approach has been adopted in several countries such as Brazil, Canada, China, Israel (in East and West Jerusalem in both Arabic and Hebrew), New Zealand and Senegal, transcending educational boundaries to impact sectors such as community development and social services. According to him, it is a way of dealing with complex challenges of equity and design. “It’s a practice to generate self-awareness and free leaders/designers from habits that perpetuate harm and inequality, changing the relationships between those who hold the power to design and those who are impacted by those designs,” he explains. “In this way, we co-create the conditions for collective liberation and transformation.”

An example of this process can be seen in a school facing high drop-out rates and a lack of student engagement, where school leaders adopt Liberatory Design. They began listening sessions with the students, discovering that many felt demotivated due to a lack of connection with the curriculum and the school environment. Based on these insights, they launch a curriculum restructuring project co-developed by students and teachers, focused on teaching methods that are more inclusive and relevant to their lives.

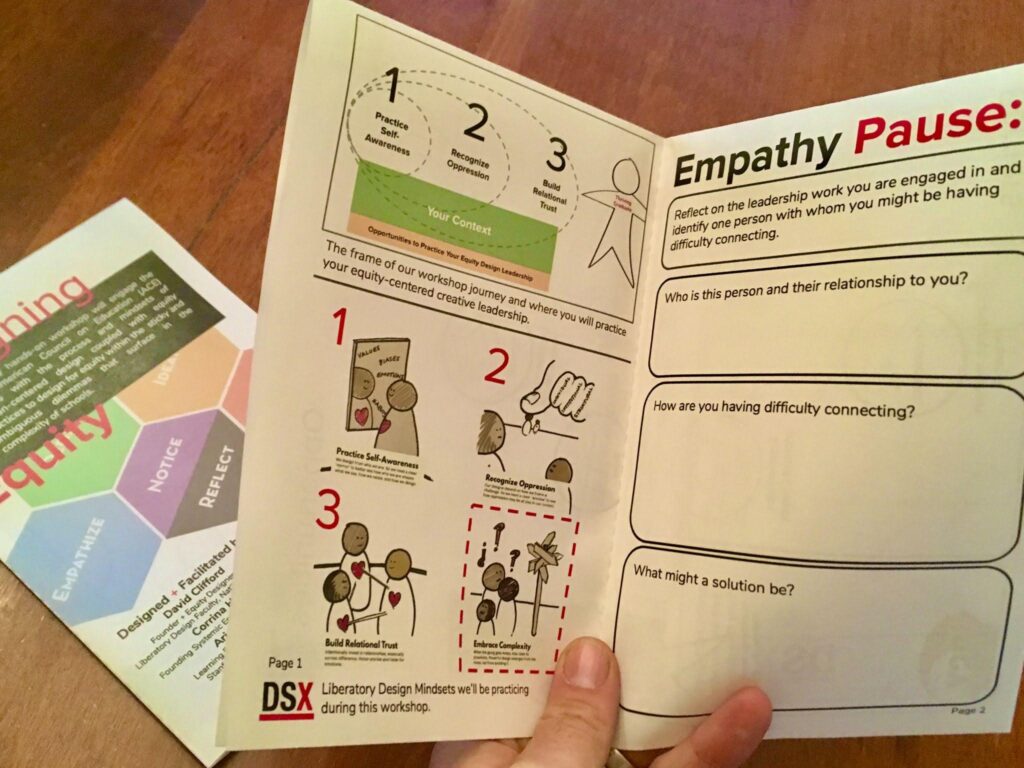

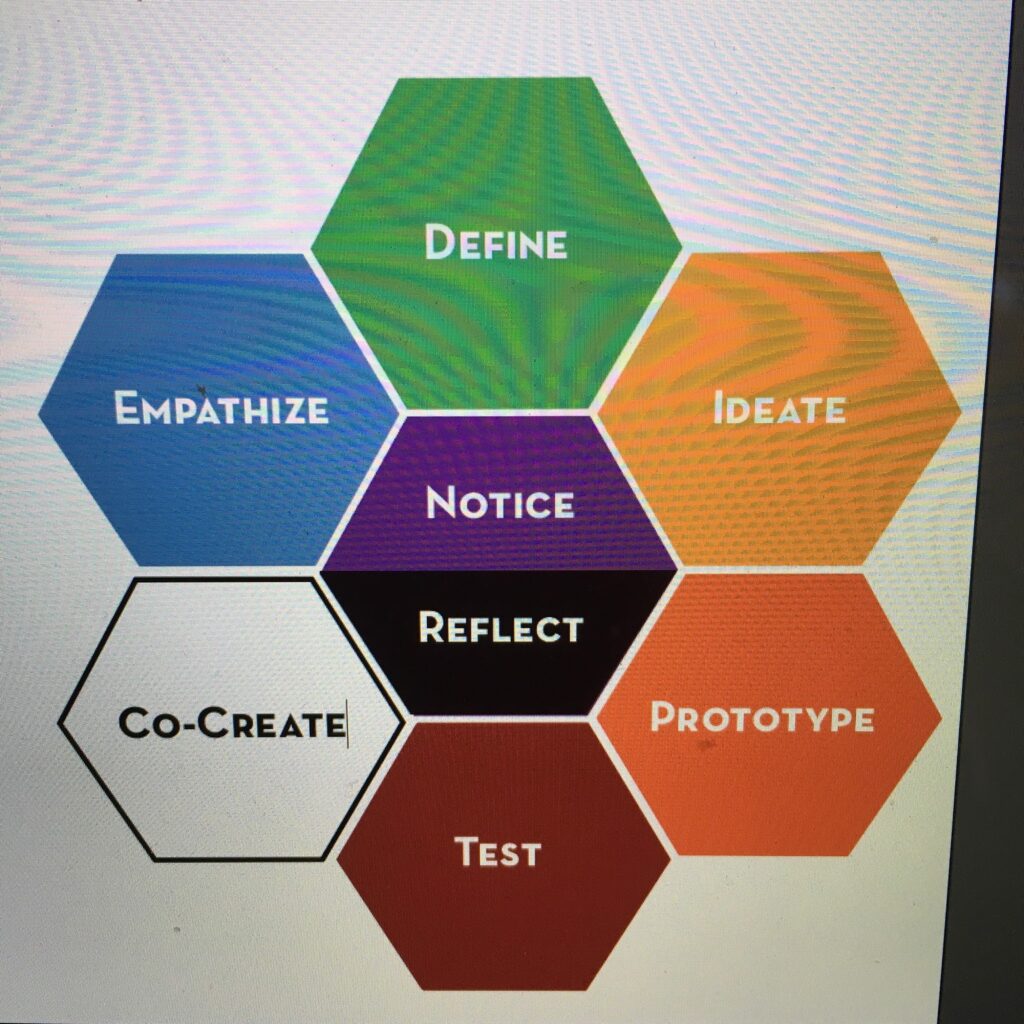

Notice and Reflect

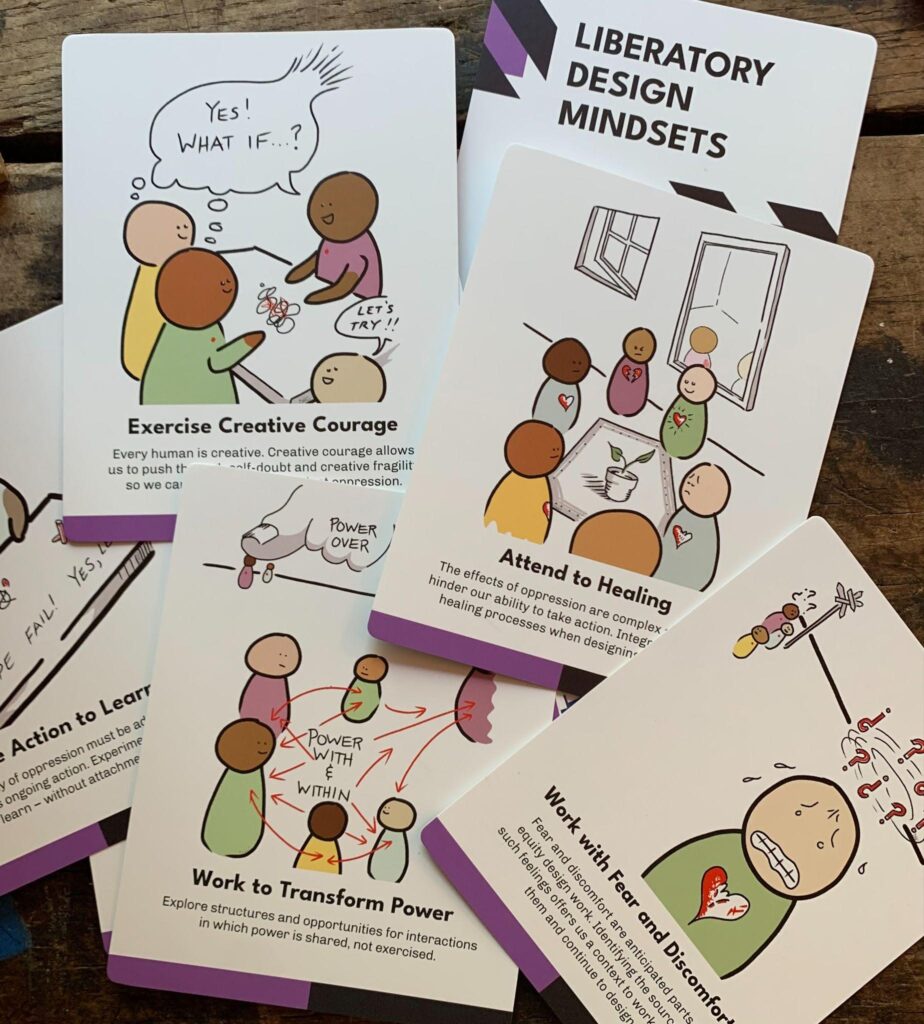

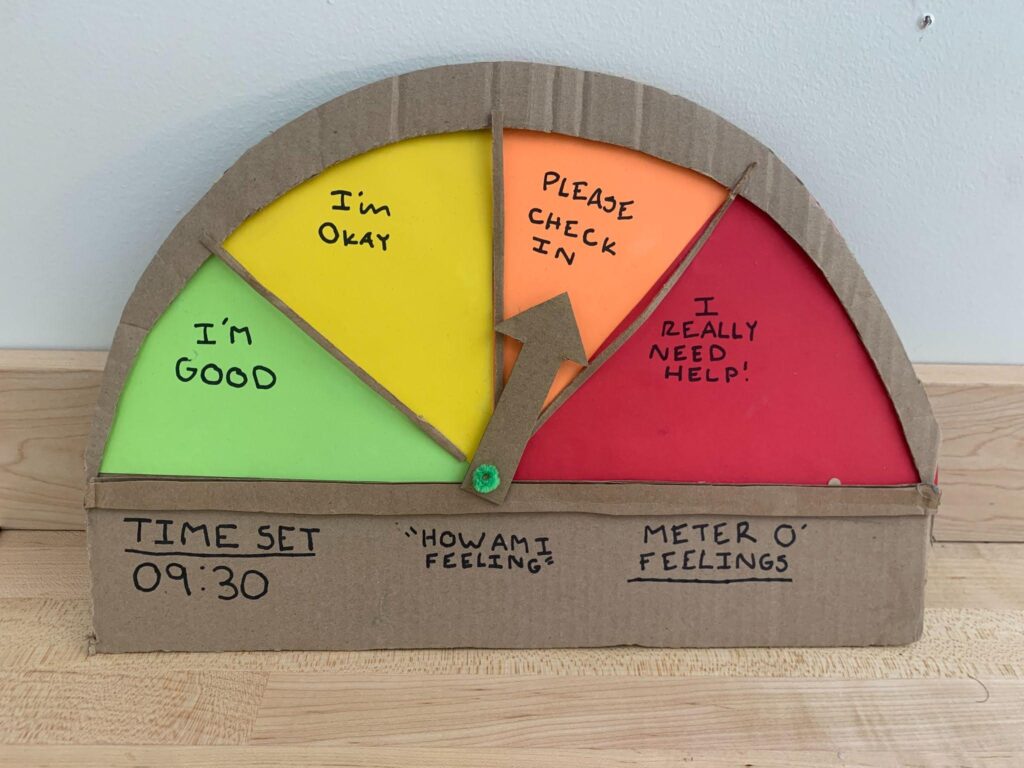

Liberatory Design emerged from the addition of two steps to the Design Thinking process: Notice and Reflect. These actions help to pause and interrupt habits of the dominant culture that contribute to inequality.

Perception and reflection are the heart of Liberatory Design and are essential to all steps of the process. Among its characteristics are a focus on equity, working to eliminate barriers and inequalities; co-creation, which actively involves affected communities in the design process, ensuring that their voices and perspectives are central; critical reflection, which encourages continuous reflection on the impact of proposed solutions, assessing how they can reproduce or challenge oppressive structures; and adaptation, promoting a continuous process of prototyping and refinement, adapting solutions to the needs and feedback of communities.

Another practical example of Liberatory Design is the development of inclusive educational programs that aim to improve equity in access to quality education for students from marginalized communities.

Susie Wise, co-creator of LD and Director of Strategy at the Alameda County Community Food Bank – a non-profit organization that provides food to more than 400 organizations in California, including soup kitchens, daycare centers and senior centers – explains that Liberatory Design is not limited to the education sector, extending to different contexts such as food justice strategies and educational leadership. “The concept of LD seeks to bring an equity lens and a complexity lens to build design practice in the community. I’m using LD to design a food justice strategy,” she says.

According to her, many designers are moved to adopt the lenses of equity and complexity to make community design work more grounded and less extractive. “I also notice that professionals with a strong racial equity orientation are moved to use the design framework as a way of structuring their collaborations in the midst of difference,” she says.

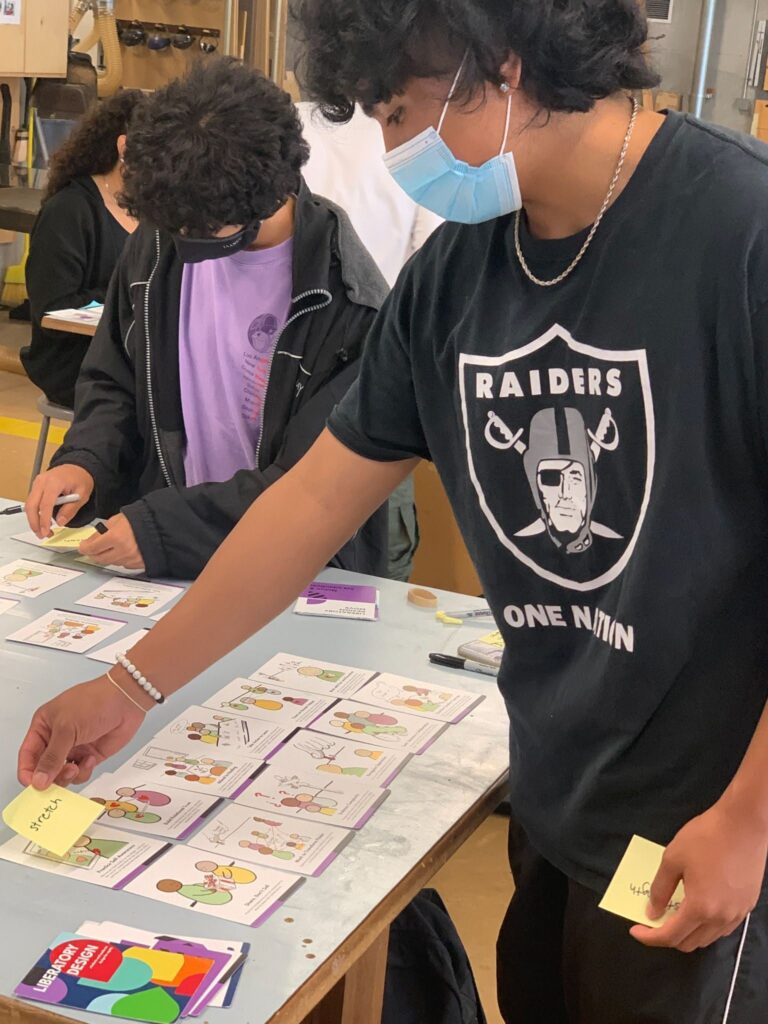

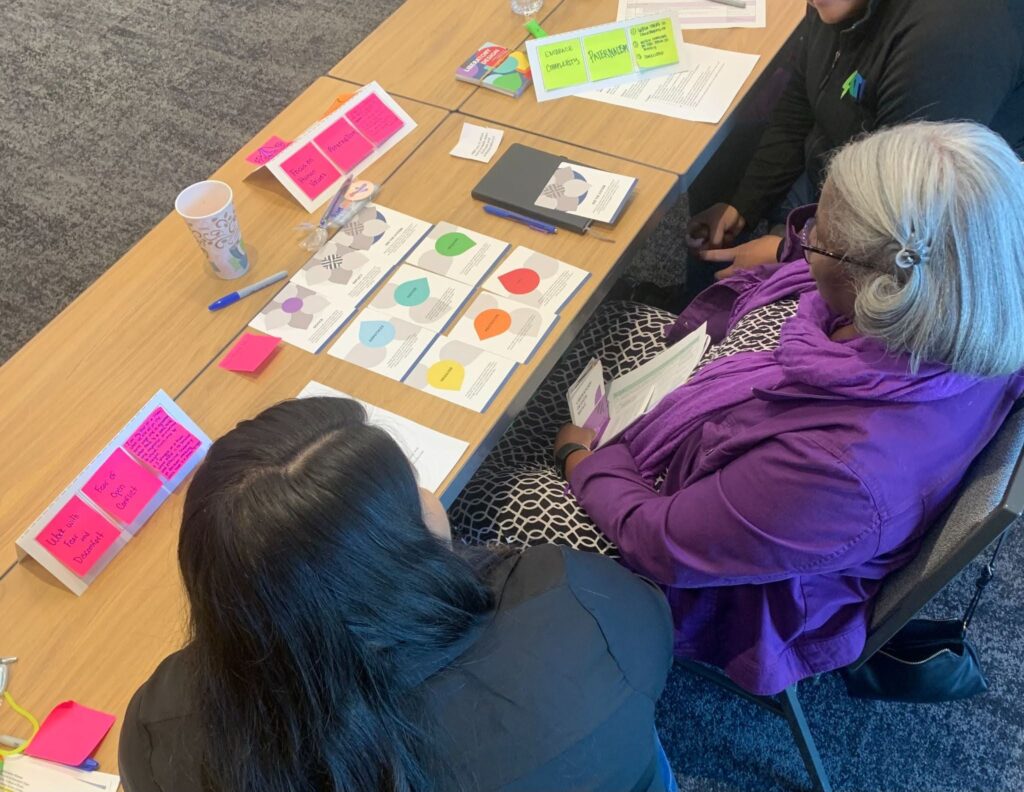

Practical experiences

Josh Hough, from Ako Ōtautahi Learning City Christchurch Trust (New Zealand), points out that Liberatory Design promotes significant cultural change, creating more inclusive and empowering learning environments and fostering a culture of openness and continuous improvement. “Liberatory Design is a powerful framework for promoting awareness, creativity, care and the ways of being and doing needed to achieve any kind of real and lasting change with and within the community. By integrating LD, teachers and administrators can create environments that nurture trust, voice, empathy and collaboration – ultimately leading to more engaged and empowered school communities whose spheres of positive impact extend far beyond the classroom walls,” she says.

Hough explains how the methodology has become a part of her daily life: “I’ve used it in many contexts where LD has been instrumental in creating a space for deep connection, reparation, joy and impact,” she says. One example is a 2021 research project highlighting the experiences of rangatahi takatāpui (young Māori who identify with diverse genders, sexualities and sexual characteristics). “The research shares voices of rangatahi takatāpui, and the use of LD in conducting the research helped create an outcome that provokes and invites educators to change their relationships with takatāpui from sympathetic to empathetic and transformative.”

Dr. Tracy Rone is Assistant Dean, Research and Community Partnerships, School of Education & Urban Studies at Morgan State University in Baltimore (USA), an HBCU (Historically Black University/College, which are colleges founded on the belief that every individual deserves access to higher education; traditionally, they are colleges geared towards African Americans). Dr. Rone says that Liberatory Design is being used to redesign educational programs for school leaders, promoting community involvement and equity. According to her, through LD, public school teachers and administrators can benefit from developing empathy and gaining insights into the perspectives of children and their families, teachers, administrators and community members.

“We are using Liberatory Design to redesign one of our graduate programs, a Master of Science (M.S.) in Educational Administration and Supervision, which prepares school leaders to serve as school principals, especially in under-resourced public school districts in the region,” she says.

According to Dr. Rone, school systems often function as “silos”, with central office, schools, families and the community existing as separate entities, and with children and families – the very people schools are supposed to support – having less visibility, voice and access to power. “At the heart of how we use LD is centralizing the voices of our students and alumni, to better understand their experiences and needs that will best support them as disruptive and liberating leaders, and also family members and caregivers in local schools, so that schools can create strategies to mitigate the legacy of economic, housing and environmental inequality.”

In Long Beach (California), Dr. Nader I. Twal is the administrator of the Vision 2035 Program, the strategic plan of the Long Beach Unified School District, and there LD is being used, among other objectives, to reduce racial inequality.

According to Dr. Twal, black students were not well served by the systems currently in place and, regardless of the initiative taken, the results continued to be unequal. “This required us to interrogate a deeper historical context, which may need more intentional redesign, along with those most impacted by these outcomes.”

To that end, the program team engaged in “robust listening sessions across the city to gather the dreams and hopes of Black students and communities.” Different ways were worked on with Liberatory Design, while community members were invited to dream and imagine what services the Center could offer, how it could be physically structured and how it could be organizationally structured, and even how it should “look”, to that honored the rich history of our black community, according to Dr. Twal.

Liberatory Design is not just a methodology, but a movement towards more equitable futures, as noted by David Clifford, for whom “LD was designed with a lot of love and liberation”, reflecting a commitment to creating design spaces that respect human dignity and promote the active participation of everyone involved.

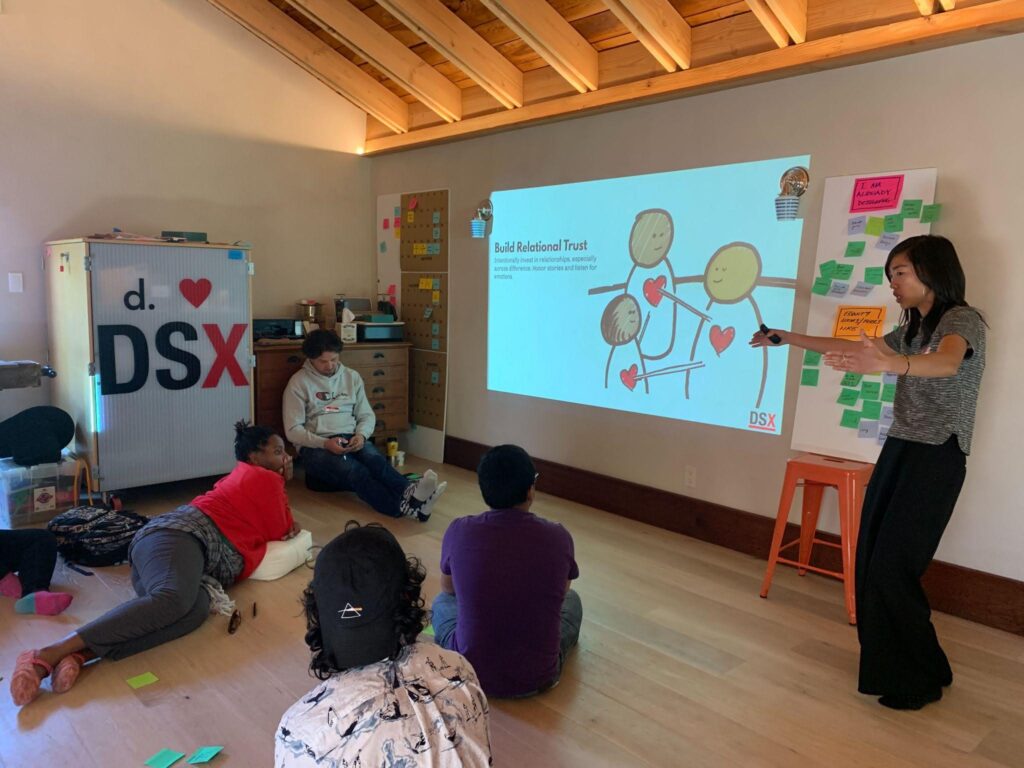

And it has one more advantage, according to him: it allows for joint work anywhere. “My favorite part of Liberatory Design is being able to work with people around the world, like Ana and Thais in Brazil [representatives of Escolas Criativas], or Tharaa and Dana in Jerusalem, to translate/release/pollinate Liberatory Design within these contexts. What I love is practicing Liberatory Design to seek collaboration and build relational trust so that LD can be truly authentic to the context.”

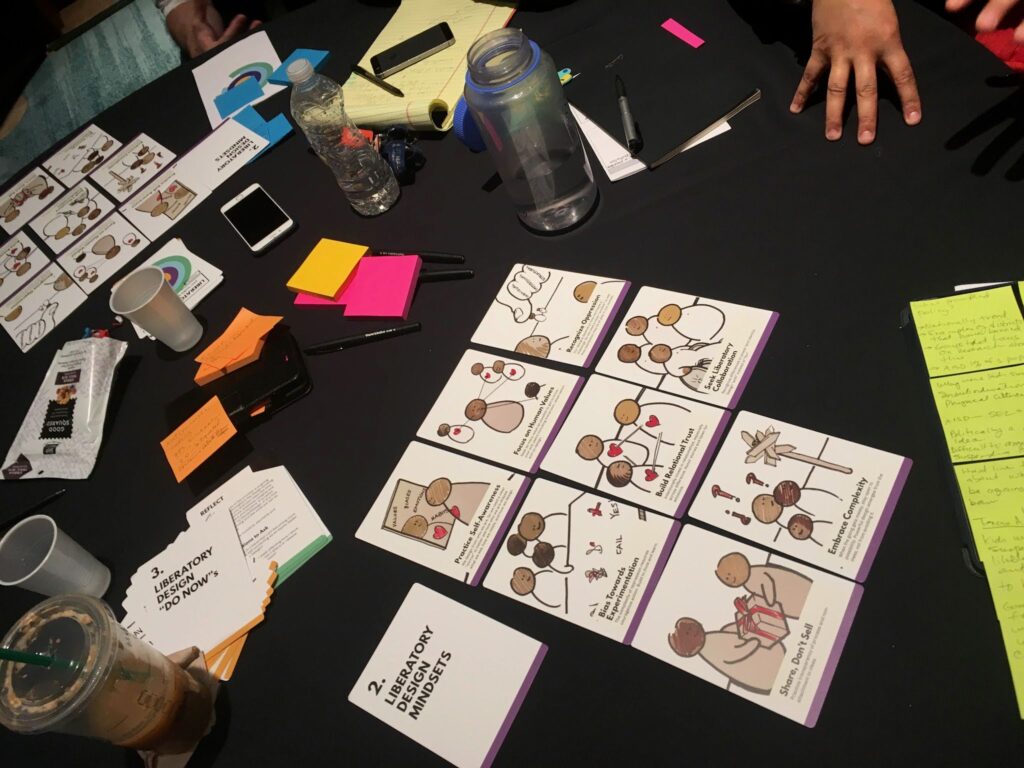

How LD works in practice

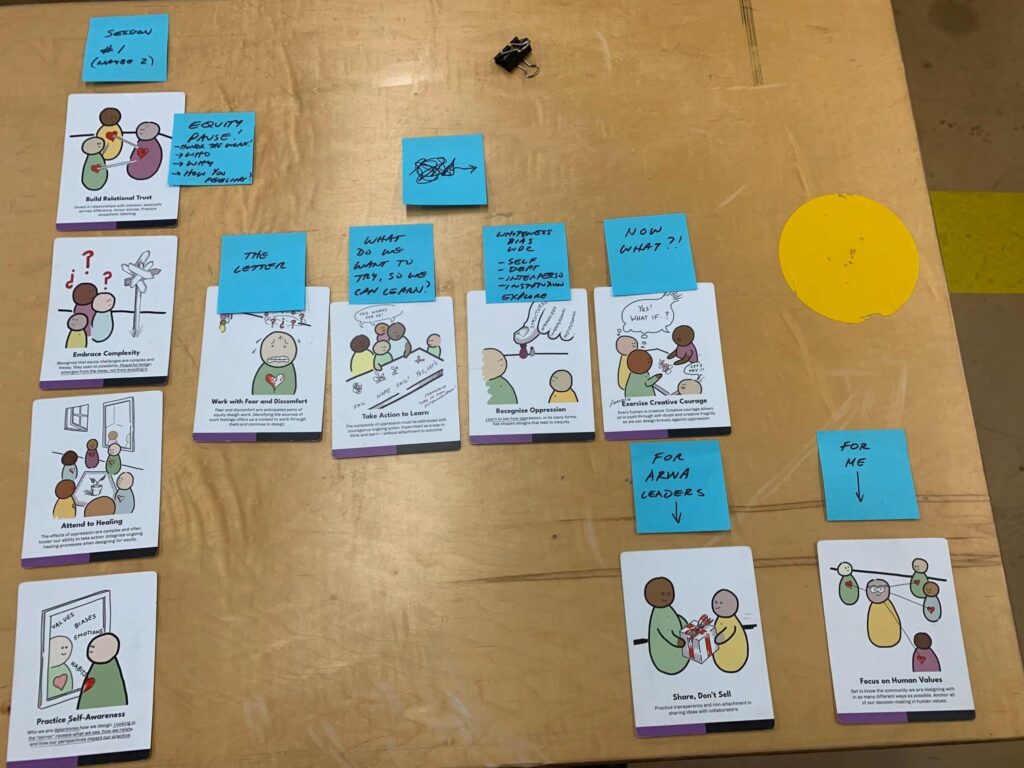

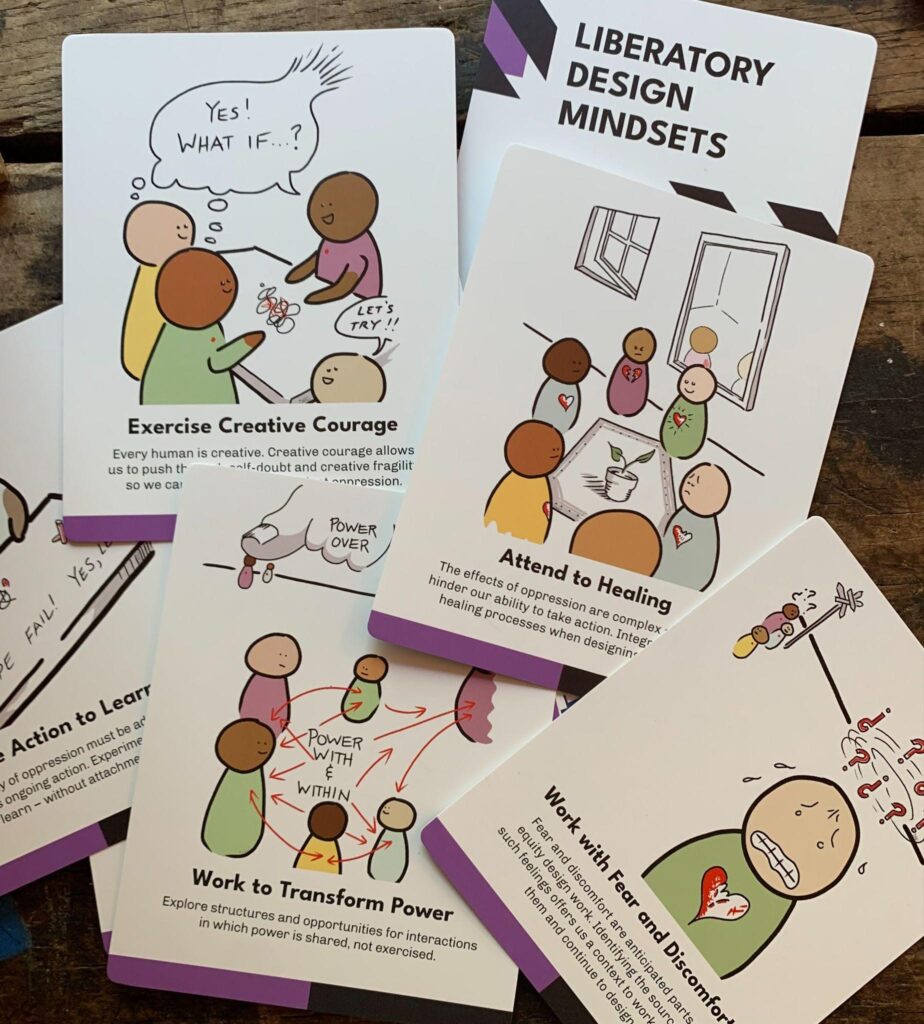

Active Listening and Deep Empathy – Educators and school leaders use Liberatory Design to engage in active listening with students, parents, and community members. Rather than assuming solutions, they start by deeply understanding the experiences, needs and aspirations of those affected. (Liberatory Design Mindsets of Practice Self-Awareness, Focus on Human Values)

Co-creation of Solutions – Based on the insights collected, a collaborative process begins. Students, educators, parents and community members are invited to actively participate in defining challenges and generating ideas. This co-creation environment not only validates the experiences of the people involved, but also triggers a sense of ownership and commitment to the proposed solutions. (Liberatory Design Mindsets of Work to Transform Power, Seek Liberatory Collaboration, and Share, Don’t Sell)

Continuous Adaptation – Design Libertador is not satisfied with single or quick solutions. Instead, it promotes a continuous cycle of experimentation, feedback, and adjustments. This allows solutions to evolve as they are tested in practice and refined based on stakeholder feedback. (Liberatory Design Modes of Notice, Reflect, Inquire and Prototype, as well as the Mindsets of Share, Don’t Sell and Take Action to Learn)

Systemic Implementation and Evaluation – The solutions developed are implemented not as isolated experiments, but as part of a larger educational transformation strategy. Continuous assessments ensure that changes are not only effective, but also sustainable in the long term. (Liberatory Design Mode See the System, Inquire, Notice and Reflect, as well as the Mindset of Recognize Oppression)

Impact and Empowerment – As solutions begin to show positive impact, the community becomes increasingly engaged and empowered. Students feel more connected to school, parents become active partners in their children’s education, and educators develop new leadership and collaboration skills. (Liberatory Design Mindsets of Build Relational Trust, Attend to Healing and Exercise Creative Courage)

Do you want to learn about the material and put Liberatory Design into practice?

Access the translated material in our library, just click here.

Explore the Liberatory Design Libertador website, visit: https://www.liberatorydesign.com/